The beginnings of the Manhattan Project can be traced to early science and technology research into uranium-238 conducted at the University of California, Berkeley. U-238 is the most common radioactive element, making up about 99 per cent of the Earth’s supply of uranium.

Uranium-238 does not sustain a fission chain reaction, however, and must be modified into an isotope that can. It can be bombarded in a nuclear reactor to make U-235, the fuel used for the Hiroshima bomb. That isotope was made and separated at labs in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

In 1941, a University of California chemist named Glenn Seaborg created an element with an even greater potential for explosive power. Since the previously discovered uranium had taken its name from Uranus and neptunium from Neptune, Seaborg named his discovery plutonium after the planet Pluto and, coincidentally, the Greek god of the dead.

Not knowing which fuel successfully could be manufactured or incorporated into a bomb, the United States decided to pursue both. A secret site near the remote eastern Washington hamlet of Hanford was chosen to make plutonium.

Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves was chosen to manage the Manhattan Project because of his engineering, administrative and organizational abilities, according to Robert S. Norris, author of Racing for the Bomb, General Leslie R. Groves, The Manhattan Project’s Indispensable Man.

Groves had the right credentials for the job. He boasted a military background and was well connected to both Washington decision-makers and America’s top industrialists. The son of an Army chaplain, Groves was born in Albany, N.Y., on Aug. 17, 1896. Destined for a military career, he entered West Point in June 1916 and graduated No. 4 in the class of November 1918 under a curtailed wartime curriculum. Groves also graduated from the Command and General Staff College and the Army War College.

Selecting the Corps of Engineers upon graduation, Groves served at various military camps throughout the South, in Washington, D.C. and in Nicaragua, where he helped survey a proposed inter-oceanic canal. After more than two decades of commissioned military service, Groves began to prove that he had extraordinary project management, leadership and technical skills. The Second World War was to be his platform.

In 1940, Groves was promoted to colonel and was appointed the special assistant responsible for domestic military construction. He moved through the military and Washington ranks quickly, masterfully manoeuvering through Washington’s bureaucratic labyrinth. The project that elevated Groves to a superstar among Washington bigwigs was supervising the construction of the Pentagon, which began on Sept. 11, 1941, and was completed on Jan 15, 1943.

But Groves was only involved in the Pentagon project during its early stages. On Sept. 17, 1942, he was selected to run the Manhattan Project – the most expensive and mammoth construction project ever staged. Groves was truly indispensable in the construction of the atomic bomb, and was the critical person in determining how, when and where it was used on Japan.

Groves’ appointment was the result of his drive and determination. Having served with distinction under some of the Corps of Engineers’ most qualified officers also lent credibility to his reputation. In detailing his subject’s contribution, Norris presents a compelling case that, of all the participants in the Manhattan Project, Groves alone was indispensable to its success.

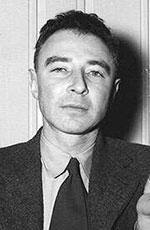

Groves made all the important decisions governing the Manhattan Project. Over the objection of virtually every adviser and scientist, he personally recruited J. Robert Oppenheimer, scion of a prosperous family of clothing merchants, as his scientific director. Oppenheimer was a highly controversial figure and a known communist.

Groves also hired other giants of American industry to construct and run the atomic factories. Groves drew up the plans for the organization, construction, operation and security of the project, and took all necessary steps to put it into effect. Reporting directly to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Gen. George C. Marshall, he routinely bypassed traditional lines of authority to ensure the success of his project.

Once Groves got the go-ahead to build an atomic bomb, he didn’t waste a second. “He knew how to get things done, which was a prized skill in the federal government,” says Cameron Reed, a professor and chairman of the physics department at Alma College in Alma, Michigan, and an expert on the Manhattan Project. “Having come up through the ranks, Groves was very connected. He knew contractors all over the country. His first day on the job, he acquired the site at Oakridge, Tennessee – approximately 50,000 acres to build uranium-separation plants. And he negotiated labour contracts for tens of thousands of labourers who were recruited for the project.”

Knowing that his factories would consume extraordinary amounts of electricity, Groves built power plants that were capable of generating enough electricity for 1/8 of the state of Tennessee. Most remarkable, according to Reed, was Groves’ confidence in his abilities.

“Many of the projects he undertook during the Manhattan Project were tested in laboratories, but never on an industrial scale,” says Reed. “Groves actually winged it, developing the technology as he went along.”

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.