Believe it or not, the movie musical Grease turns 40 this summer.

Believe it or not, the movie musical Grease turns 40 this summer.

It’s no exaggeration to say that it took the 1978 box office by storm. Indeed, the radio-ubiquitous title song caught the mood of the moment perfectly: Grease is the word.

Alas, the simple joys can never stay simple. In the fraught temper of our times, Grease’s enduring appeal now poses a conundrum for those disposed to view everything through an ideologically-tinted lens.

Grease originated as a 1971 Chicago stage production, written by Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey. Based on Jacobs’ own high school experience, the original has been described as a “raunchy, raw, aggressive, vulgar show.” Given that its subject matter deals with 1950s working-class teenagers and their grappling with adolescence, sex, romance and peer pressure, such a characterization shouldn’t come as a surprise.

I saw the Broadway production in December 1975 and found it good fun. You could be offended if that was your predisposed reaction, but only the very naïve would deny that it struck a realistic chord. Although most 1950s teenagers didn’t think and behave exactly like that, there was still a material element of truth to the ethos presented on stage.

En route to the big screen, Grease inevitably underwent changes. In the pungent estimation of Atlantic essayist Michael Callahan, a “salty musical was frothed into a sweet milk shake.”

These changes didn’t necessarily sit well with all the original creators. Jacobs, for instance, was concerned that the movie was sanitizing the grit out.

Still, cinematic needs must win out and producer Allan Carr got his way. It isn’t for nothing that Hollywood has been referred to as the dream factory.

So the locale was shifted from the industrial Midwest to sunny California; four new songs were imported; and half of the original score was either dropped or relegated to background. And in order to accommodate Olivia Newton-John’s inability to consistently project an American accent, the virginal heroine Sandy was transformed into an Australian expatriate.

For Newton-John, the movie was fortuitous.

Courtesy of her exceptional good looks, pleasant voice and a series of genre-crossing hit records, she’d enjoyed a lucrative mid-1970s in North America. Pop music fortune, however, is notoriously fickle and the hit string was pretty much played out by the time the movie came to market.

Grease changed that.

Thanks to Grease’s enormous popularity and the related evolution of her public image – the hitherto sweetness being supplemented by a tongue-in-cheek naughtiness – Newton-John was now set for another high-earning half-decade. Bigger, in fact, than before.

Forty years on, Grease perturbs some people. Jacobs may have been worried about the grit being ironed out of his creation, but the movie is apparently too risqué for a certain kind of 21st century sensibility. Or to be more precise, its protagonists’ attitudes towards sex are out of sync with the current politically-correct zeitgeist.

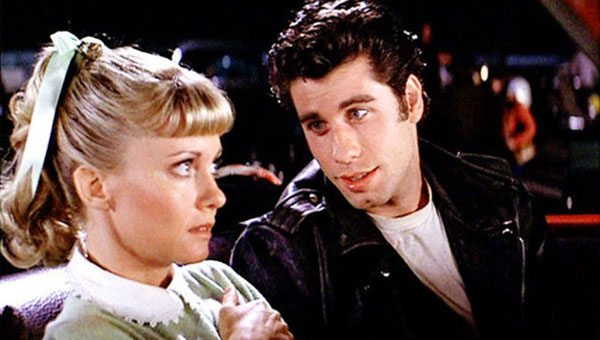

Some wonder whether a specific line in the song Summer Nights is “an endorsement of date rape.” And the scene where Danny (the John Travolta character) persistently tries it on at the drive-in with Sandy (Newton-John) is deemed “questionable.”

Oh, dear! Can nothing be left alone?

Two things.

First, the sexual attitudes on display in Grease were reasonably representative of the era’s teenage mores. Being a movie and not a moral primer, it was certainly exaggerated for effect. But most people who experienced the period would relate to the goings-on.

And second, Grease has always had an enormous female audience. This is hardly the mark of something that’s offensive, threatening or hostile.

A recent U.K. Guardian article noted how “In today’s climate, rewatching the classics with an eye on gender politics can be an unsettling experience, unseating old favourites, and Grease is at the heart of a raging debate as to whether the film is sexist, or feminist, with a surprising amount of fervour in each corner.”

That, I suggest, is the nub of the problem.

Whether it’s Grease or anything else, movies made decades ago shouldn’t be expected to reflect the attitudes, anxieties or foibles peculiar to 2018. They’re creatures of their own time.

The 20th century English novelist L.P. Hartley got it right: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”

So bottom line, the answer is: Yes. Grease is still the word.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.