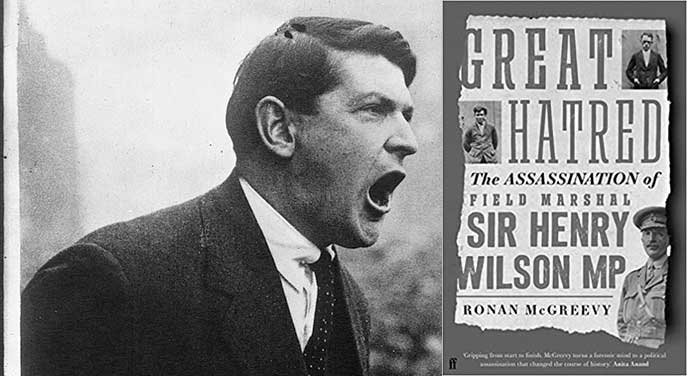

Michael Collins was the most dynamic figure in the events leading to the establishment of the Irish Free State. And he was killed in an ensuing civil war ambush on August 22, 1922.

Michael Collins was the most dynamic figure in the events leading to the establishment of the Irish Free State. And he was killed in an ensuing civil war ambush on August 22, 1922.

Just two months earlier, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson had been assassinated in London. Allegedly, Collins ordered the hit.

Irish journalist Ronan McGreevy’s new book Great Hatred: The Assassination of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson MP postulates a direct link between the two events. He characterizes Wilson’s murder as Ireland’s Sarajevo, thus seeing it as precipitating the Irish civil war. To quote: “If Wilson hadn’t been shot, Collins wouldn’t have been shot.”

(The Sarajevo reference is to the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which set in motion the proximate chain of events leading to the First World War.)

Collins and Wilson were both Irishmen, albeit with very different perspectives. What they had in common were strong opinions and a capacity for unequivocal ruthlessness. If they thought circumstances called for lethal force, then lethal force it would be.

|

Related Stories |

| Fenians used Canada as an Irish revolutionary pawn

|

| Was Oliver Cromwell the Great Satan?

|

| Digging for the bones of a lost Irish hero

|

| More in Books |

Born in County Cork, Collins was a Catholic nationalist determined to separate Ireland from the United Kingdom. He played a key role in the 1919-1921 War of Independence and was still a couple of months shy of his 32nd birthday when he died.

Wilson, a native of County Longford, was a Protestant unionist with a diametrically opposed view on the question of Ireland’s relationship with the U.K. His long military career took him to the very top of the British army.

Time, however, has treated the two men very differently.

Collins is one the most prominent figures in Irish history, fondly seen by many as the “lost leader.” Although deeply controversial, his profile has risen over the years. He was even the heroic subject of a major 1996 Hollywood movie.

Wilson, in contrast, is a largely forgotten figure. And when he’s remembered at all, the terms are often unflattering, if perhaps inaccurate and unfair.

Is McGreevy right? Did the Wilson killing cause the Irish civil war that subsequently took Collins’ life?

The answer is yes and no. Like Sarajevo, it was an immediate trigger. But the Irish civil war was coming anyway.

Although Collins had negotiated and signed the December 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, its terms generated substantial opposition among many of those who had fought in the preceding War of Independence. The fact that the agreement enjoyed majority popular support cut no mustard with them.

Instead, they saw the treaty as a betrayal of everything they’d dreamed of. They wanted a full-fledged Irish republic right away, and that wasn’t what they were getting. When push came to shove, democratic niceties were thus dispensable.

Prior to Wilson’s shooting, Ireland was already divided into two armed camps, each with its own physical footprint. Collins was the most important figure on the side of the new Irish government, but those opposed to the treaty refused to accept the state’s legitimacy. It was a standoff that couldn’t persist indefinitely.

Meanwhile, the British authorities in London were getting very antsy. They saw the standoff as a repudiation of the treaty and wanted the Irish government to put its foot down.

Then came the Wilson killing.

A former Chief of the Imperial General Staff gunned down on his own doorstep! And in broad daylight! It was an outrage!

So the British blamed the anti-treaty forces and demanded the Dublin government move against them immediately. Six days after Wilson’s death, the government took action and the Irish civil war was officially on.

If Collins ordered Wilson’s shooting, his motive remains a matter of speculation. As an ardent opponent of the Irish revolution, Wilson had been on a hit list during the War of Independence. But killing him in 1922 was a different matter. Collins, after all, was a senior figure in the new Free State government and no longer a revolutionary on the run.

But regardless of the British reaction to Wilson’s death, the Irish civil war was likely to happen. No government – particularly one in a brand new state – can indefinitely tolerate an intransigent and armed opposition that seizes territory.

And as National Army Commander-in-Chief, Collins would’ve been an obvious target once hostilities broke out. Still, his death wasn’t necessarily foreordained.

The truth of the matter is that the specific set of circumstances leading to the fatal ambush was a function of recklessness. You might even call it hubris.

Maybe romantic heroes are built to self-destruct.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.