Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative explores his ideas on poverty alleviation and education reform

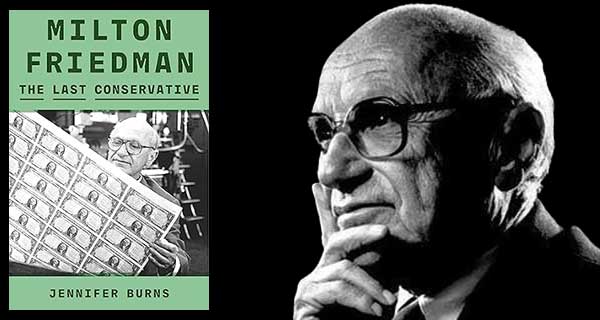

Prompted by Jennifer Burns’ new biography Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, my previous column focused on Friedman’s role as a disrupter of the post-war Keynesian consensus on economic policy and the related revival of money supply management as a key economic determinant. But as noted, there was much more to him than that.

Prompted by Jennifer Burns’ new biography Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, my previous column focused on Friedman’s role as a disrupter of the post-war Keynesian consensus on economic policy and the related revival of money supply management as a key economic determinant. But as noted, there was much more to him than that.

While his Nobel Prize was in economics, his policy interests ranged much further, extending into broad areas of American life. Temperamentally and intellectually, he wasn’t the kind of guy to stay in any narrowly defined lane.

For instance, Friedman first floated the concept of a guaranteed annual income as far back as 1939, subsequently returning to it in his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom. The desirability of government action to alleviate poverty was something he readily accepted; there should be “a floor under the standard of life of every person in the community.”

His suggested approach was novel: a negative income tax to be administered through the federal income tax system. Poverty was a function of people lacking money and the way to address it was to have the tax system make up the difference between a person’s income and whatever minimum standard society was willing and able to provide.

|

| More book reviews |

| A captivating exploration of the world of emperors

|

| The month John Diefenbaker’s political goose was cooked

|

| From blooms to gloom: the surprisingly exciting history of horticulture

|

Friedman wasn’t interested in dictating how the poor should spend their money, or how they should live their lives. He believed the existing welfare system involved an “intolerable degree of paternalism” and social worker snooping, so he envisioned replacing it entirely.

This antipathy towards state intrusion in people’s lives was a core principle of Friedman’s worldview. To quote Burns, “Capitalism and Freedom was suffused with a general horror of anyone telling anyone else what to do.” As we’ll see, it wasn’t a characteristic she always approved of.

Burns describes the negative income tax as the “first of Friedman’s ideas to be co-opted by the liberal establishment,” sometimes without any acknowledgement of paternity. And championed by liberal intellectual Daniel Patrick Moynihan – who deemed it “a spanking good idea” – it became a key part of the Nixon administration’s ill-fated Family Assistance Plan proposal.

Eventually, though, the negative income tax “was reborn as the Earned Income Tax Credit (ETIC), a rebate for low-income Americans.” Enacted as a temporary measure in 1975, it was made permanent in 1978 and subsequently expanded.

Education was another area Friedman jumped into, starting with a 1953 paper that, to quote Burns, “seemed a quintessentially academic exercise: float a radical idea and hope it went somewhere.”

Public funding for education would be reformed to give parents vouchers enabling them to purchase “approved educational services” for their children. The financial value of those vouchers would be equivalent to the cost of educating a child in the public system. By thus providing options for those trapped in underperforming public schools but unable to pay for conventional private education, Friedman hoped to encourage choice and competition – two things he highly valued.

However, the waters got muddied a year later when the Supreme Court outlawed state-enforced segregation and various Southern legislatures looked for ways to do an end-run around the decision. Suddenly, vouchers had a new constituency, one that saw them as a backdoor means of maintaining segregated schools.

For his part, Friedman didn’t like the way “his idea had been hijacked by political opportunists.” But beyond calling it “a bad solution,” he didn’t take issue with it. While he was opposed to state-enforced segregation of any sort, how people and groups wanted to voluntarily organize themselves – including where they sent their children to school – was their private business.

Burns comes down heavily on him for that. Still, she acknowledges consistency on his part. Although the Friedmans were Jewish, he didn’t question the right of individuals to be antisemitic. Recalling an incident involving one of his own children, she puts it this way: “Even with his son in the cross-hairs, Friedman would not abandon his principles.”

Other areas where he was publically active included drug legalization (he was for it) and the U.S. military draft (he was against it). In a late-life interview, he characterized his contribution to ending the draft as his “most important accomplishment” in the policy realm.

Friedman’s intellectual brilliance is generally acknowledged, even by those who deplore his influence. Whatever one thinks of him, Milton Friedman was indisputably his own man.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.