Was Thomas Becket, perhaps subconsciously, simply in search of sainthood and martyrdom?

An extraordinary event happened on July 12, 1174. Henry II, king of England, submitted to a penitential flogging at Thomas Becket’s Canterbury Cathedral tomb. Administered by the Canterbury monks, the punishment was in response to Henry’s role in Becket’s murder less than four years earlier.

An extraordinary event happened on July 12, 1174. Henry II, king of England, submitted to a penitential flogging at Thomas Becket’s Canterbury Cathedral tomb. Administered by the Canterbury monks, the punishment was in response to Henry’s role in Becket’s murder less than four years earlier.

The fatal feud between Henry and Becket has been portrayed as reflecting the divide between Norman and Saxon in the wake of the 1066 Norman Conquest of England. But that’s not really the case.

Becket wasn’t Saxon. Both of his parents were from Normandy, the region of north-western France settled by Vikings in the 9th and 10th centuries. Rather than a quarrel between conqueror and conquered, the feud was about the power-related competition between Crown and Church.

Becket was born into modest circumstances. To quote journalist/historian Dan Jones: “The king had found him working as a clerk in the service of Theobald, archbishop of Canterbury. He had plucked him from obscurity and promoted him as the face of the most ambitious royal family in Europe. Becket rose to the task. He excelled in royal service.” In 1155, Henry appointed him as chancellor.

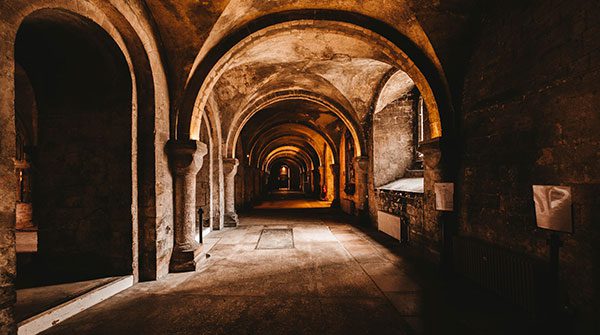

Canterbury Cathedral |

| Related Stories |

| The death of King Richard the Lionheart

|

| The power life of a medieval heiress

|

| Legend, reality and the Outlaw King

|

Although often described as friends, the relationship between the two men wasn’t one of equals. Becket was 13 years older and undoubtedly aware of the source of his prominence. If he wasn’t, Henry was apt to remind him.

The turning point came in 1162 when Theobald’s death created a vacancy in Canterbury. Henry spied an opportunity. He would see to it that Becket was appointed archbishop in Theobald’s place, thus putting his loyal protégé at the head of the wealthy and influential English Church.

The move wasn’t at all popular with the Canterbury monks, who claimed the traditional right of electing their archbishop. And Henry’s shrewd mother, the dowager Empress Matilda, advised against it. But Henry insisted. So Becket was ordained a priest on June 2, 1162, and consecrated archbishop the following day.

What could go wrong? As it transpired, everything.

Becket was suddenly his own man, not the king’s. Perhaps the inherent dependency of his previous position had rankled deeply. Perhaps he was stung by the criticism from those who believed him unworthy of the Canterbury archbishopric and set out to prove them wrong. Or maybe his intrinsic religiosity was set free, and the real Becket could assert himself.

Whatever factors were at work, the consequence of his transformation was dramatic. Henry and Becket were on a collision course.

Almost from the get-go, Becket set out to assert ecclesiastical independence, even if it meant figuratively poking a finger in Henry’s eye. Thus feeling betrayed and keen to establish royal authority, Henry chose his battleground on the issue of “criminous clerks,” the practice whereby religious clerks could escape secular punishment by invoking a right to be tried in ecclesiastical court rather than the normal criminal justice system. Henry wanted that changed, and the disagreement escalated to the point of Becket fleeing to extended exile in France.

The French king, Louis VII, and Pope Alexander III initially supported Becket, but their patience wore thin. Being men of the world, they sought a compromise solution. Becket, however, dug in.

And although an uneasy truce was eventually established, it didn’t last.

As part of his succession planning, Henry wanted his eldest son crowned as a kind of co-king and arranged for the archbishop of York to do the job. Outraged by this violation of Canterbury’s hitherto lock on coronation, Becket excommunicated the prelates involved, which enraged Henry and prompted four of his knights to track Becket down in Canterbury, brutally murdering him on December 29, 1170. Defiant to the end, Becket’s last words proclaimed his willingness to die for the Church.

Henry’s temper was legendary and popular rendering claimed that the words prompting the murder were clear: “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” Not everyone agrees. For instance, historian Simon Schama believes Henry’s venting was more ambiguous, along the lines of a complaint that no one would protect him from being “treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!”

In any event, the murder of an archbishop at prayer shocked Western Europe; Canterbury became a popular pilgrimage destination and Becket was canonized in 1173. Then acknowledging his role while denying any murderous intent, Henry presented himself for penance on July 12, 1174.

In addition to questioning Becket’s judgement, it’s not unreasonable to wonder about his motivation. Was he, perhaps subconsciously, in search of sainthood and martyrdom?

If so, he succeeded.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

Suggested reading:

Becket by Jean Anouilh: A play which dramatizes the conflict between Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England leading to Becket’s murder in 1170. It was written in French and has been translated into multiple languages.

Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot: A verse drama that portrays the final days before Becket’s murder.

Thomas Becket: Warrior, Priest, Rebel by John Guy: A biography of Thomas Becket, focusing on his complex relationship with Henry II and the events leading up to his death.

The Quest for Becket’s Bones by John Butler: A fascinating exploration of the mystery surrounding the location of Becket’s remains after his murder.

Who Murdered Chaucer?: A Medieval Mystery by Terry Jones, Robert Yeager, Terry Dolan, Alan Fletcher, and Juliette Dor: While this book is primarily about the mysterious death of Geoffrey Chaucer, it provides some interesting historical context about the time period, including the murder of Thomas Becket.

The Lives of Thomas Becket by Michael Staunton: This book offers translations of the primary texts describing Becket’s life, death, and legacy.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.